Well...after many months of designing, re-designing, updating, mind changing and revamping I give you the…

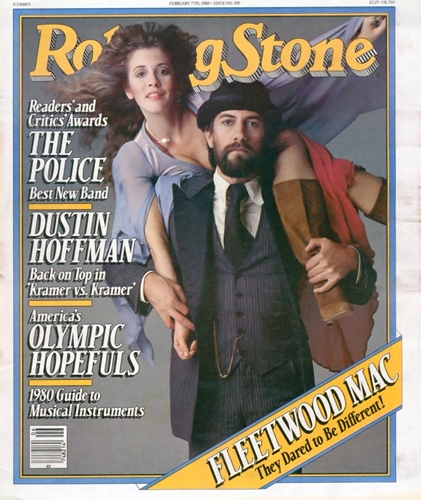

Rolling Stone Magazine Issue #310

On this day in 1980 Stevie Nicks and Mick Fleetwood graced the cover of Rolling Stone…

FIVE NOT SO EASY PIECES

Fleetwood Mac is more than the sum of it’s parts

Stevie Nicks is in the bathroom of her publicist’s office on Sunset Boulevard, fixing her hair. She can get all of her thick, shag-cut tresses to stay on top of her head with a single pin, she tells me. Sure enough, she has them coaxed into a neat, Victorian-style topknot in less than fifteen seconds with three strokes of a borrowed brush. “If you stop to think about it,” she explains, “it never works.” A short drive down Sunset, inside a film soundstage that once housed lavish production numbers, the rest of the Fleetwood Mac entourage is gathering for tonight’s rehearsal. It was officially scheduled to begin at 4:30, and it’s past six now, but nobody here seems particularly concerned. People traipse in and out. A buffet dinner is waiting. A Japanese masseur kneads someone’s shoulders. Two women ride bicycles, round the perimeter of the studio (which is the size of a small airplane hanger) while a tiny, shaggy dog runs alongside them. In two weeks, Fleetwood Mac’s nine-month-long world tour, their first in over a year, opens in Pocatello, Idaho. “That’s Lindsey. It’s perfect,” says a tall woman standing next to me.

She introduces herself as Lindsey Buckingham’s sister-in-law, Eileen. Lindsey is at the dinner table a few feet away from us, facing a half-eaten plateful of food while doodling with a guitar that’s in his lap. “When I first met him, he was about nineteen. And he had his guitar, always. He played all the time.” Of course, when Eileen met Lindsey, he was not playing a custom-built electric guitar with a built-in transmitter that sent his every random riff ricocheting through a column of loudspeakers.

Someone tells me that John McVie hasn’t been feeling well, so when we are introduced, I ask him if his cold is better. He is shaking my hand with both of his. “It isn’t a cold.” “Well, then I hope your stomach is better,” I offer, running down the list of typical health problems. “It’s, uh, lower than that.” We both giggle in embarrassment, then joke about late-night TV commercials for Preparation H. McVie laughs easily, but there’s melancholy in his smile: Emmett Kelly with an electric bass. After five minutes of conversation, I notice we’re still shaking hands.

Mick Fleetwood strides through this assemblage of pets, friends, relatives and crew personnel, a man with a mission. Eighteen years of the rock & roll life have not eroded his English boarding-school composure. “I am always aware of what I’m doing,” he tells me later.

Right now, he is collecting the other band members for a meeting to choose which songs will be included in the tour set, and what the order will be. Shortly, McVie, Fleetwood, Christine McVie, Buckingham and Nicks (who has since arrived) are sitting cross-legged on the floor of the soundstage, huddled in caucus.

Meanwhile, Sharon and I are having a talk; Sharon is Stevie Nicks’ friend, a beautiful, dark-eyed girl of about twenty-two who looks as if she floated out of a Gauguin. Sharon used to live on Maui, and she sang lead in a rock & roll band that played clubs and hotels. Until one night last year, when Nicks happened to be in the audience. “She jumped up onstage and sang with me,” Sharon recalls, blushing. “We did all her tunes.” Sharon left her band. Now she lives in Stevie’s house in Los Angeles. They work together making demos, and Sharon is Stevie’s wardrobe mistress for the tour. “Stevie says that this will be like an education for me,” she explains. The meeting concluded, Christine McVie whips by on a bicycle. “You see,” Sharon continues, “when the tour is over, I’ll never have to wonder what rock stardom is like. I will have seen that for myself.”

It’s just another day in Los Angeles, California, to all of the Day of the Locust characters ambling up and down Hollywood Boulevard; just one more October afternoon when the bright, high sun makes the stars cemented in rows along the pavement seem to sparkle like polished hubcaps. The kids lined up with their autograph books and their Cheryl Ladd T-shirts in front of Frederick’s of Hollywood know better. Today is Fleetwood Mac Day in Los Angeles, by special proclamation of the office of Mayor Tom Bradley. And today, a Fleetwood Mac star will be dedicated on Hollywood Boulevard after a short, traditional ceremony. Inside Frederick’s, the band is being presented with commemorative underwear. Outside, a crowd of about 200 is gathered in the street and in two sets of bleachers set up along the sidewalk. A pair of loudspeakers blares Rumours, the 1977 album that sold 15 million copies worldwide, more than any other LP by a single group in recording history. Fleetwood Mac’s new album, Tusk, will be unveiled tonight at a record-company party; it is an ambitious, double-record set that took thirteen months and cost over a million dollars to make. Alongside the bleachers are sidewalk vending machines filled with today’s Los Angeles Herald Examiner; there are ominous headlines about a stock-market tumble that may signal a coming recession. One wonders if today is a good day for the release of ambitious double-record sets that list at $15.98.

“Making a double album is something that I wanted very much to do,” Mick Fleetwood told me earlier. “We have three songwriters, and it is hard for them to develop their different aspects without room…they’re artistically stifled. That’s why people leave bands, you know.”

Maybe the band members should rub the tummy of Holly, the Autograph Hound— Bill Welsh, the master of ceremonies at this 156th Star Presentation, says that it brings good luck. Holly, an unidentified person in a dog suit, bobs and weaves through the crowd while fifteen members of the University of Southern California Marching Band file through the front doors of Frederick’s playing “Tusk.” (One hundred twelve members of the USC Marching Band played on the single.) Mo Ostin, president of Warner Bros. Records, steps up to the platform microphone and makes a speech in which he says, “I don’t think we can measure how important Fleetwood Mac has been to Warner Bros., and to the record industry in general.” What he does not say—and what is on the minds of more than a few people at Warner Bros., and the record industry in general—is that there is quite a bit riding on the success or failure of Tusk in the marketplace. Ostin finishes his speech, and one by one, the band members come up to the mike to say thank-yous.

“Thank you for being…uh…Americans,” John McVie deadpans. Stevie Nicks follows, her white satin skirt swirling. “Thank you for believing in the crystal vision,” she says quickly, a little disconnected. “Crystal visions really do come true.” Crystal visions come true. The more I learn about the members of Fleetwood Mac and their entourage, the more I find myself struggling with notions I thought I dismissed years ago: karma, destiny, karass, hand of fate. The relationships—and not necessarily the sexual ones—among the members of the band and the people around them are as complicated as the plot of a Russian novel. For example, seven years ago, close buddies Lindsey Buckingham, Tom Moncrieff, Richard Dashut and Stephanie Nicks lived together in a small house in Los Angeles. Now, Buckingham and Nicks are in the band, Dashut is their coproducer and Moncrieff most recently played bass for Walter Egan’s band—which Buckingham has produced—and helps Stevie make demos. Twelve years ago, Buckingham played bass in a bar band in Palo Alto, and his number-one musical hero was Brian Wilson. Now he knows Wilson, has discussed music with him, and his fellow band member, Christine McVie, is about to marry Brian’s brother Dennis. Sixteen years ago, Mick Fleetwood quit boarding school and went to live in his sister Sally’s flat in London. He’d been playing drums for three weeks in her garage when a keyboard player, Peter Bardens, who lived across the mews, heard him and wandered over. Through Bardens, Fleetwood met guitarist Peter Green, and eventually the two formed the original Fleetwood Mac.

Tonight, Sally Fleetwood Hartnoll will arrive from London and watch her brother play drums in a room that is much larger than any garage. Of course, there is that most unlikely set of circumstances—does anybody not know this melodrama by now? A California singer/songwriter couple makes one album that goes nowhere. The engineer of the recording studio where the album was made plays it to demonstrate his studio’s capabilities for the leader of a British band that is having personnel problems. The bandleader likes the studio, and likes the duo even better. In the middle of their New Year’s Eve Party, in 1974, the couple gets a message—do they want to join a band? The newly re-formed version of Fleetwood Mac makes a record (Fleetwood Mac) that is one of the largest selling in Warner Bros.’ history. The couples in the band—Buckingham-Nicks, McVie-McVie—break up in 1976, but the band carries on. The next album sells 15 million copies. There is something romantic in these stories of interlocking lives, chance encounters and bonds that do not break when hearts do. Dreams do not always come true, and the idea that a rock & roll band can be a community, an extended family, seems faintly silly in 1980, like patchouli incense sticks. And yet, you want to believe in a Fleetwood Mac. Just as a child wants to believe his divorced parents will reconcile, or a teenager wants to think his high-school gang will endure beyond graduation, just as we all would like to see John, Paul, George and Ringo together onstage again, one more time. People are saying that Tusk is Fleetwood Mac’s White Album, and in some ways, the comparison appears reasonable. Each song on Tusk is immediately recognizable as the work of a particular songwriter, and there is very little musical overlap between McVie’s breathy love tunes, Buckingham’s playful rock & roll and Nicks’ extended confessional poems. But the White Album was the product of a band that was in the process of disintegrating, each song a shard from a broken mirror. Tusk is more like a puzzle. You get the feeling that if you spent enough time with this album, and this band, you could figure out how and why the pieces fit together. Or at least why you wanted them to. The rehearsal studio is damp, dark and cold, the kind of chill that makes you think you’re about to come down with the flu. “Fleetwood Mac is a job,” Nicks says to me at one point. “It’s a wonderful job. But there are some nights when I just do not want to go to that rehearsal hall.” After sitting around with the band for several hours, I understand what she means. Even with the masseur, the bicycles, the friends and family, the food, the fully stocked bar, there is nothing fun about working all night on songs you’ve played hundreds of times before.

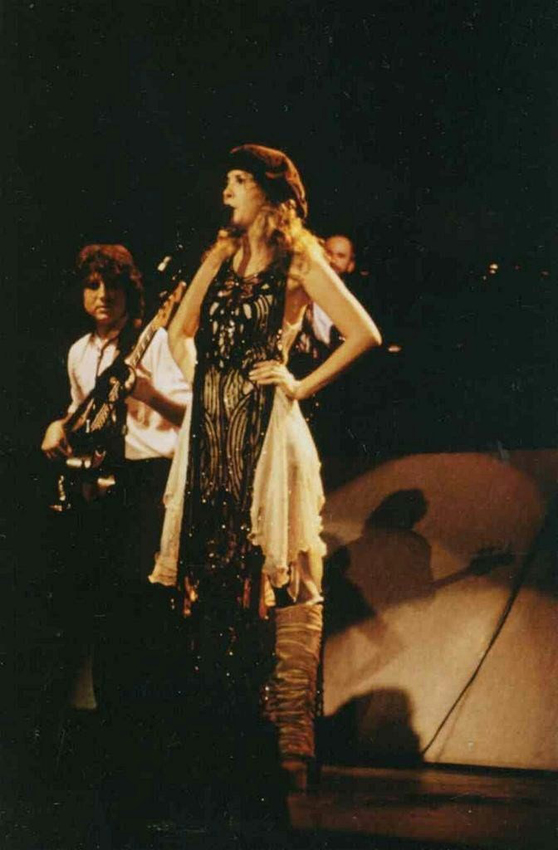

Time passes, slowly. The band works for a while onstage, breaks, then each member drifts off to a separate corner of this cavernous building, like planets drifting off into deep space. In the dark isolation, you lose track of the sequence of events, but you remember pictures: there is Christine McVie, dressed in black, thinner and paler than her photographs indicate, sitting on the floor of the stage, dwarfed by her banks of keyboards. “Do I have any free time this week?” she asks pleadingly, looking up at the road manager. There is Nicks, in high heels, long satin skirt and dancer’s woolen leg warmers, scampering offstage in the middle of songs when she isn’t needed, then huddling in conversation with two or three of her women friends, who always seem to be close by. There is John McVie, chain-smoking, half-hidden behind amplifiers, playing bass lines constantly, whether Fleetwood and Buckingham care to jam or not.

There isn’t much conversation besides what needs to be said to get the job done. It’s not that this rehearsal isn’t friendly; it’s just that these people seem to have evolved beyond camaraderie. They’ve spent too much time with each other, though lately not so much. Buckingham, casually passing by Fleetwood, stops to ask him what he did after the record-company party last night. “We definitely transcended. Ended up jamming with Curry (Grant, the lighting director) till the wee hours. Actually, we were playing one of your songs, from Buckingham Nicks,” Fleetwood says, mentioning the album that prompted him to ask Lindsey and Stevie to join the band five years ago.

“Oh, really?” Buckingham says, suddenly interested. “Which song?” “Uh…I forget the name,” says Fleetwood sheepishly. “Was it ‘Don’t Let Me Down Again’?” “Nooooooo….” “‘Without a Leg to Stand On’?” “Nooo….well, I’m not sure,” Fleetwood answers. “It could’ve been. Yeah.”

They smile politely and Buckingham goes his way, Fleetwood his. The song “Tusk,” like Romours’ centerpiece, “The Chain,” is an assemblage of pieces; ideas that didn’t go anywhere until they were attached, almost as a whim, to other ideas that didn’t go anywhere, some late night in the recording studio. “Tusk” started out as a drum riff that Fleetwood played onstage to warm the band up before the opening of every concert. Buckingham wrote words and a melody to it, then set it aside. Later, in the studio, Fleetwood’s drum riff found its way onto another song that never got completed. Instead, Buckingham and coproducer Richard Dashut took a twenty-second section of the drum track, sped it up and rerecorded it over and over to make a rhythm bed for what eventually became “Tusk.”

As Buckingham explains it, the twenty-second section of drums was “enough tape to go all the way across the board to the other side of the control room. We had to have someone in the middle of the room holding the tape up to make sure it didn’t sag, then we made a copy, from one twenty-four-track machine to another, of this huge, sped-up tape loop rolling around the room.” The idea for the USC Marching Band came from Fleetwood, who’d been enchanted by a brass band he’d seen at a village celebration in northern France that summer; the Trojans’ track was recorded live at the USC football stadium, then added. Fleetwood also came up with the word tusk. It had been his slang term for a certain male appendage, and by coincidence, the album package designed by Peter Beard came back with elephant images all over it. “Tusk” emerged from these bits, brainstorms and splices; this is the way Fleetwood Mac seems to work best. The creative process, the collaboration, doesn’t take place in group jams but on tape, in the studio. In fact, the way this band works, it isn’t necessary or even expedient for them all to be in the studio at once, ever. Only two of the tracks on Rumours, Dashut says, were played and recorded at the same time. In other words, virtually every track on that album is either an overdub or lifted from a separate take of that particular song. What you hear on the record is the best pieces assembled, a true aural collage.

And yet, Rumours and Tusk can hardly be called sterile records; they may be made with the most advanced equipment platinum can purchase, but they sound human, quirky, less than perfect. When I try to imagine what Studio D, Village Recorder, Los Angeles, was like during the thirteen months Fleetwood Mac was in residence, I don’t conjure up pictures of engineers huddled over the printout of a digital machine, debating the perfect millisecond in which to make their splice. The picture that sticks in my mind is of Buckingham and the engineers standing in the corners of the studio, holding that thirty- foot-long ribbon of tape as it weaves around the room. All this technology so they can play with tape like it was a giant cat’s cradle, and make hit singles from brass bands and jungle noises. Lindsey Buckingham, telling a story, about his childhood: “We were in the fifth grade, my friend and I, and we had a little section of my backyard that was just all woods. Very small. My friend and I had just been to Disneyland, and we went on the jungle cruise. When we got back, we went out into the backyard, and dug a little river, filled it with water from the garden hose and made our own jungle. It was great—we even had sound effects. I dragged a speaker from the record player out there and put on a sound- effects record so we’d have noises: Ooook ooook akkkk! Jungle noises. I don’t think many kids did things like that.”

One night, sometime before they began working on Tusk, Lindsey Buckingham went over to Mick Fleetwood’s house in Bel Air to talk. Buckingham won’t say the meeting was a confrontation, but from the way he tells the story, you get the feeling something very heavy passed between them, that he said things that had been bubbling under the surface for quite a while. Early on, during the making of Rumours, Buckingham says he’d gotten frustrated that his songs weren’t coming out the way he “heard them in my head. And Mick just said, ‘Well, maybe you don’t want to be in a band.’ It was a black-and-white situation.” Buckingham swallowed his objections, and Fleetwood Mac went on the road in 1977 and stayed on tour an entire year. Sometime during that tour—in Philadelphia, he thinks—Buckingham blacked out in the shower of his hotel room. He was rushed to a hospital, given all kinds of tests, and it was discovered he has a mild form of epilepsy, which is now under control. Sometime during that same tour, he began carrying around an eight-track Tascam tape recorder. Using “all the bathrooms of the country” for echo chambers and Kleenex boxes for snare drums, he put together six or seven songs of his own. That, he says, got his confidence up. “When it came time to go into the studio, I just had to stick my neck out. I told Mick that I wanted to put a machine in my house, to work on my things there. I had to pursue things that were in my head, and not be intimidated into thinking they were the wrong things to do.”

Buckingham grew up in Atherton, a comfortable, conservative California suburb, and attended college in the late Sixties, a combination of factors that has produced a personality that is at once self-disciplined and spacey. His older brother won a silver medal for swimming in the 1968 Olympics, and Buckingham remembers being awed by his strict routine.

“He’d get up at six in the morning, work out, go to school, work out till dinner, go to sleep and start all over again.” Buckingham never “got into that”—he grew long hair and joined a rock band. But Buckingham’s schedule while he was working on Tusk wasn’t all that different from his brother’s—up in the morning, working on tapes at home, afternoons and late nights in the studio, all to capture the music he was “hearing in his head.”

Sometimes, according to Mick Fleetwood, Buckingham would get so serious, so wound up, that he’d just disappear for two days. “You have to allow yourself to get totally drawn into the music,” Buckingham explains, his blue eyes flashing intently. “Once you’re there, the hardest thing to do is let yourself do anything outside that. I’d come out of my basement studio after about six hours, and Carol, my girlfriend, would be sitting in the living room watching TV or something, and I just wouldn’t have much to say. My mind would be racing. I love it.” Several of his Tusk songs were recorded almost entirely in his basement, with Buckingham playing all the instruments. “‘The Ledge’ was crazy…there are about four or five vocals there that are not particularly tight, and all of them were sung in my bathroom. I stuck the mike on the floor and did them down on my knees.” He did a lot of vocals that way, he says, and he gets down on the floor to demonstrate. “I did it just because I liked it. Because it sounded weird.”

Another story from the Fleetwood Mac history book: In the autumn of 1973, Mick Fleetwood discovered that his then-wife, Jenny, was sleeping with the band’s guitarist, and Englishman named Bob Weston. Fleetwood’s discovery was particularly inopportune because the band was just beginning a long American tour to promote the album it hoped would be its first big commercial success here, Mystery to Me. Fleetwood fired Weston, the band broke up temporarily, and Fleetwood went to Africa, alone. (Meanwhile, the band’s manager, Clifford Davis, hastily slapped a group of pickup musicians together, dubbed them the “New Fleetwood Mac,” and sent them out on the road in place of the real Mac so he wouldn’t have to cancel the already-booked tour dates. The bogus Fleetwood Mac tour was a disaster. The real Fleetwood Mac sued Davis for damages and won after years of litigation.) The whole story gives you a good idea of how resilient Mick Fleetwood is. He returned from Africa, put his marriage and his band back together, and without any business experience, took over as manager of the group he and John McVie started in 1967. Fleetwood Mac would continue to have financial problems, personnel changes and love troubles, but the band would never fall apart again; the bonds might crack, but they would not break. Fleetwood was the glue. “You have to have a pivot point when there’s five people wandering around,” he says with certainty. “No one else thinks about things like where to record, where we’ll play on tour, whether we’ll make a single or a double album—they don’t particularly want to. And I do.”

Fleetwood is bone thin, over six feet six and has a penetrating, slightly frightening gaze; one imagines him in a black waistcoat, a headmaster in a Bronte novel. This afternoon, we are sitting across a table from each other in the offices of Penguin Promotions in Hollywood, which also houses Seedy Management (Fleetwood Mac’s organization) and Limited Management (which supervises the solo career of ex-Mac guitarist Bob Welch, among others). Along with his role as drummer in his band, Fleetwood supervises all aspects of Penguin’s businesses. “I like working,” he says, and tosses off the suggestion that he is “hard-nosed.” “I may crack a whip every now and then,” he chuckles, “but I don’t crave command. I’m exactly the way I was at school.”

School, for Fleetwood, was Sherbourne, a proper British boys academy. He was sent there by his father, Mike Fleetwood, a wing commander in the Royal Air Force. “I was absolutely hopeless in classes. I still don’t know my four times tables. And I’m pushed to repeat the alphabet. I don’t read books; I’ve read two in my life. But I get along very well with people. I was always being put in charge of things. I like that.” He leans forward, striking a theatrical pose. “Look, this band doesn’t always get on like Gleem adverts, everything all bright and sunny. This is a healthy compromise. If it needs someone hitting a Kleenex box instead of me hitting snare drums, then we’re going to hit the Kleenex box!” He pauses long enough for me to ask him what the two books were. “The books I read? Oh…Sherlock Holmes—I remember I had to read that one for class. And Alice in Wonderland.”

“I feel a little like Alice in Wonderland up here.” Stevie Nicks is in bed, recovering from a root-canal session, propped up in a mountain of pillows. You have to take a running jump to get up on the bed with her—it is an antique four-poster, with a thick mattress about three feet high. I sit across from her, at the foot, and think of The Princess and the Pea. And of the nineteenth century, for Nicks has a lot of the qualities one generally associates with ladies who wrote sentimental fiction and poetry in Victorian England. She is the kind of woman who keeps a journal. She is the kind of woman who wakes up too early in Buffalo, New York, on the morning after a concert, and so writes a long verse about what she sees outside her motel-room window. She believes in fairies, runs a large, mock-Tudor house in the hills above Sunset that’s always full of visiting friends and relatives; she studies ballet and composes songs about seeing her “reflection in the snow-covered hills.” She is thirty-one years old. Nicks grew up in California and Arizona, the only daughter of a well-to-do corporation president. Her grandfather, A.J. Nicks, a country & western singer, sparked her love of music, and her mother, Barbara, introduced her to the world of fairy tales and fantasy. “She was very protective of me,” Stevie says. “All out of love. But I was kept in more than most people were.” Years later, Nicks is still protected from the outside world– -only now, her guardians are road managers and friends. “I don’t want to be so spoiled that I can’t carry on my life when there’s no more Fleetwood Mac. I’m not gonna stop doing things. I don’t want to be Cinderella anymore,” she tells me. A tiny poodle jumps into her lap. The puppy coughs, piteously. “Poor Ginny…she just can’t get used to this air in Los Angeles. I’m real nervous about her.”

She lifts Ginny, gently, by the neck. There is a thin, pinkish scar across the poodle’s belly. “She just had a hysterectomy, and I’m afraid she’s gonna open up the incision from all that coughing.” A few minutes later, Stevie’s younger brother, Chris, comes in. They confer briefly and come to a decision. That night, Ginny is put on a plane and sent to their mother’s house in Phoenix. Stevie takes me downstairs to her music room because she wants to show me what her songs sound like before they are arranged by Buckingham. “I write my songs, but Lindsey puts the magic in, and there’s no way…well, I could pay him ten percent. I could walk up to him and thank him. If I were to play you a song the way I wrote it and gave it to them, and then play you the way it is on the album, you would see what Lindsey did.”

The music room is dark; there are antique lamps draped with shawls, but she does not turn the lights on. And the tapes she ends up pulling out of her library are not rough Fleetwood Mac demos but works-in-progress for her solo project, a film and soundtrack album based on the myth of Rhiannon, the Welsh witch. Earlier in 1979, Nicks signed on as a solo artist with Modern records, a label headed by former boyfriend Paul Fishkin and Danny Goldberg. For a while the move prompted rumors that she was preparing to leave Fleetwood Mac.

“The legend of Rhiannon is about the song of the birds that take away pain and relieve suffering,” she says. “That’s what music is to me. I don’t want any pain.” She puts a cassette in the deck and sits down cross-legged on the carpet, between the stereo speakers. The music begins; a gentle roll of piano chords. Nicks’ own version of “Rhiannon” is softer, more emotional than Fleetwood Mac’s. “It’s not a rock & roll song,” she says, closing her eyes.

When the tape ends, she rummages in a drawer and pulls out a collection of photographs, her “private stash.” “This is Rhiannon, without a doubt.” The picture is of Nicks, onstage with the rest of Fleetwood Mac, in her witch costume. But it does not look like her, and I say so. “Well, you see, it turns. It goes right into…” She pulls out another photograph, of herself onstage with Lindsey. “This is the killer. And the pale shadow of Dragon Boy, always behind me, always behind me.” She is speaking almost to herself, in a hoarse whisper. “You see, I just want to make you realize that when I get carried off, really carried off into Rhiannon, it doesn’t necessarily mean I’m not carried off into Fleetwood Mac. ‘Cause I’m just as carried off into them. Rhiannon has to wait. She just has to wait; that’s all there is to it.”

I ask Stevie why she refers to Rhiannon as she. “Well, because…I don’t know why. She is some sort of reality. If I didn’t know she was a mythological character, I would think maybe she lived down the street.” Rehearsal starts very late tonight. When I get there, a little past 8:30, some powerful Afghanistan pot is being circulated, and a couple of people are trading long hits off a bottle of Harvey’s Bristol Cream. Stevie is not around yet, neither is Christine, and the buzz around the crew is that neither of the women is feeling very well. John McVie shows up on crutches with a cast covering his left leg from the ankle to just below the knee. “I got drunk and kicked a door,” he says whenever anybody asks. On a blackboard by the studio door is the schedule of rehearsals for the next two weeks; eight more left. Over this list, someone’s scribbled: IT’S NOT THAT FUNNY, IS IT?

Some time later, McVie arrives, then Nicks. The band plays “Say That You Love Me,” the first song planned for the set, and it does not go well. Christine has a bad cold, and is trying to save her voice, but nobody else seems to be able to muster the enthusiasm to compensate. Then, without a word, Fleetwood takes up the slow, steady drumbeat to “Chain.” One by one, without stopping to think about it, the rest of the band falls into place: Buckingham on guitar, then John McVie, then Christine, then Stevie, all with such a sense of purpose that suddenly everyone else in the room has stopped talking. “Chain,” more than any other song, is the story of Fleetwood Mac, their only five- way collaboration, finished long before the wounds of the celebrated breakups had a chance to heal. And watching them play it now, I realize how powerful it is. Never break the chain. For a while, I have been trying to summon the nerve to ask these people one question: what are you still doing here? The song ends, leaving a scary, charged silence in the hall. Right now, there seems to be no reason to ask.

In an hour or so, things are edgy again. New material isn’t working out. Serious drinking is under way. Stevie Nicks comes over during a short break. “That song!” She is talking about “Go Your Own Way,” Buckingham’s song.

“The harmony part is too high and I have to hurt and strain every time I sing it.” She is upset, a little tipsy. She leans forward and whispers something to me in a voice that seems too silly to be serious. “Now, I want you to know—that line about ‘shacking up’? I never shacked up with anybody when I was with him! People will hear the song and think that! I was the one who broke up with him.” She smiles conspiratorially. “All he wanted to do was fall asleep with that guitar.” Stevie drifts away to a far corner of the hall to talk to Sharon and some other friends.

Over in the opposite corner, Buckingham’s girlfriend, Carol, is sitting on a couch, looking very sad, being consoled by Christine. Fleetwood paces the perimeter of the stage, visibly worried about something. What’s going on? Do all these emotional currents add up to anything? The band, back onstage now, plays another song. I don’t want to know the reason why I love you. Stevie, smiling, shares a mike with Lindsey; what can they be thinking? Christine looks sharply at McVie. I don’t want to know….Fifteen million people bought the album with this song on it. Maybe because part of the fascination of Fleetwood Mac is that you do want to know.

The backstage area of the Salt Palace in Salt Lake City is small, neon-lit and feels a little like a crowded elevator stuck between floors. Buckingham sits on a couch in one corner while his friend Carol dabs a small amount of makeup on his cheeks. Fleetwood, dressed in black velvet, with two balls on strings dangling between his legs, struts in front of a mirror. Tonight’s show is not sold out, and the latest word on the sales of Tusk has been disappointing (at press time, 2.5 million copies had been sold). But Fleetwood is smiling, and so is John McVie, who is over in another corner, absorbed in Mad magazine. It’s the third night of the tour, and everyone’s spirits are up. Five minutes before show time, Stevie Nicks dances into the backstage lounge, her hair piled on top of her head in a mass of gnarled ringlets. “Well, how does everybody like this?” She pirouettes. There is a hairbrush handle sticking out from the side of her head. Everybody laughs except tour manager John Courage, who pretends to be shocked. “Get back in there, Stevie,” he barks. Two roadies shove her, playfully, back into her dressing room.

Just before the cue to go onstage, Nicks approaches me in the corridor and touches my cheek, impulsively. Things on the tour have been really good so far, she says, and she’s much happier than she was during rehearsal. “This is the best rock band in the world, and I’m proud of it.” Her hand is shaking slightly when she adds, “I love this band.” The next night, John McVie and a crew member who is over six feet tall stand in the aisle of the hotel bar, blocking my exit. “Just one more drink,” they insist. McVie orders a vodka and tonic, and I try a British favorite, Pimm’s No. 1 Cup. “Drink it with soda and a slice of cucumber,” he advises. “A perfect drink for sitting on the dock, watching the sun go down. But not very alcoholic. You won’t catch me near the stuff.” Three years ago, McVie told an interviewer, “I drink too much, period…but when I’ve drunk too much, a personality comes out. It’s not very pleasant to be around.” He is not at all like that tonight—perhaps his remarriage and the passage of a few years have taken some of his edge off. At any rate, McVie is not merely pleasant; he is endearing. “I’m—let’s see, how old am I now? I’m thirty-four. I’m getting up there, yes? You look at yourself in the mirror and watch the wrinkles coming in, one by one…” After McVie finished recording his bass parts on Tusk, he took a boat and a small crew and set sail from Los Angeles for Maui while the album was being finished. “There is a point on that course, about a thousand miles out,” he remembers, “where you are farther from land than at any other point on the planet. Really puts you in your place. I went out on the deck at that point and looked around, and all I could think of was, ‘Well, John, this is how far you have to go to get away from being John McVie of Fleetwood Mac.'” He leans forward and looks into his glass. He has been John McVie of Fleetwood Mac for twelve years. By now, we are both quite wasted, to the point where it does not seem ridiculous to ask him if he is truly happy with the way things have turned out. “Happy? I’m ecstatic! I’m playing with my favorite people in the world. What more could anybody ask for?” He looks up and stares at me, hard. “I love this band.”

The Salt Lake City performance is the third one of the tour, and the ends are a little ragged. Nicks’ voice sounds strong, and the band is playing well, but they are tentative with the new material, and the pace lags. But by the time they play Madison Square Garden in New York three weeks later, the pieces have fallen into place.

Buckingham, especially, is confident and playful onstage, punctuating his “Not That Funny” with a series of whooping, David Byrne-ish no-no-no’s. “Tusk” has become a show-stopping romp, and during the instrumental jam on “I’m So Afraid,” John McVie and Buckingham get so worked up they start chasing each other around the stage, butting their heads into each other’s chests like a couple of deranged reindeer. It is a highly professional show, with good playing that is still loose enough to be fun. And yet, I feel as if something is missing. I suppose I am waiting for the electricity that occurs when band members test the limits of their relationship and discover the bonds are all the stronger for the wear. Twice that week in New York, I attend Fleetwood Mac concerts hoping for another moment like the one when the band played “The Chain” in rehearsal. There are none. Mick Fleetwood, on what he would do if the band broke up: “Darling! I’ve no idea. I’ve been asked that for years. Sometimes I think I would carry on; I probably would. People must think, ‘He’s sick. He must be kidding.’ But why not? That’s what we do. Why should it stop? “We’re already talking about making the next album. So unless there’s some secret that nobody’s telling me about…”

In a private plane that’s passing through a storm somewhere over the Rocky Mountains, Lindsey Buckingham, Richard Dashut and I are discussing Talking Heads’ Fear of Music, an album they both like a lot. Across the table, John McVie cringes when he hears the words New Wave. “Is that punk rock?” he asks, feigning horror, then slumps over and pretends to sleep. Buckingham and Dashut have never seen Talking Heads perform, so I am trying to describe what the band is like. The lead singer has spasms onstage, I explain, and the bass player and the drummer are married to each other. McVie wakes up. “Did you say married to each other? You mean, this band has a man and wife, a couple in it?” There is a long, irony-charged silence. In the back of the cabin, Stevie Nicks and Christine McVie are wrapped in blankets, asleep. The plane engines drone. McVie takes a sip of his drink and mumbles something.

“Oh. We ought to mail these people a Fleetwood Mac biography. Labeled BEWARE!”

McVie looks at Buckingham and grins. What can they be thinking about? I look outside the cabin window: snow-covered hills. And realize that I don’t want to know. Sometime later during the plane ride, Lindsey Buckingham pulls out a portfolio. He used to be an art major, he explains, and he still does artwork: photo collages he makes by tampering with Polaroid SX-70 negatives. “I’m real insecure about what I do,” he says. He takes out five or six small rectangles that are shaded with color, but do not resemble anything in particular, and spreads them out in front of him. “Having something else to do besides music that you can do all right sort of makes you feel all right about the music.” By now, he has arranged the negatives in such a way that you can see each one is only a piece of the whole work. “Most artists are insecure, I suppose. Insecure overachievers.” He lays the final negative down, and there is a completed picture on the table.